Colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer (CR-CA) is a malignant tumor disease occupying the third position among the most frequently occurring malignancies worldwide. In 2012, nearly 1.4 million new cases were diagnosed worldwide. [1] In the Czech Republic, the incidence of KR-CA is increasing year by year.[2] In addition to a high and constantly rising incidence, this disease also has a high mortality rate, mainly caused by the prevailing diagnosis of the disease only in advanced stages, when treatment procedures are limited. That is why today there is an effort to effectively screen people over the age of 50. From the point of view of prognosis and treatment, it is appropriate to differentiate colon cancer and rectosigmum and rectal cancer.

| colorectal cancer | |

| C18, C19, C20 | |

| Localization | colon and rectum |

|---|---|

| Incidence in the Czech Republic | 36.79/100,000 population. (2012) |

| Maximum occurrence | 70–80 let |

| Prognosis | see text |

| Histological type | adenocarcinoma (95%) |

| Part of the syndrome | Lynch syndrome , Familial adenomatous polyposis |

| Therapeutic modalities | surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy |

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

KR-CA is a disease occurring mainly in developed countries. The highest incidence in terms of continents is in Europe and Oceania, while the lowest is in Africa and Asia. The four countries with the highest global incidence of KR-CA in both sexes in 2012 were South Korea, Slovakia, Hungary, and the Netherlands.[1]

The Czech Republic ranks first in global incidence, both for men (4th place in 2012)[1] and women (16th place in 2012)[1] . From the point of view of long-term development in the Czech Republic, the incidence of colorectal cancer has been increasing over the past 30 years, and mortality has also increased during the same period.[3] In 2013, the incidence of malignant tumors of the colon and rectum (diagnosis C18–C21) in the Czech Republic was 76.74/100,000 inhabitants[4] and the mortality rate was 35.35/100,000 inhabitants.[4] Current information on the incidence and mortality of KR-CA in the Czech Republic can be found on the website of the Institute of Biostatistics and Analysis of Masaryk University .

Symptomatology[edit | edit source]

The clinical picture of KR-CA depends on its localization in the large intestine and the way of growth, so it can be very diverse .

The most striking manifestation is intestinal obturation , if the tumor mass fills the entire intestinal lumen - clinically, the patient presents with ileum . Earlier and not so clinically significant manifestations of intestinal obturation can be excessive flatulence, a change in the defecation stereotype , colic pain or a subileous state . It not infrequently happens that the tumor is only discovered during ileus complications.[2]

Another clinically significant manifestation is bleeding from the tumor into the GIT , either microscopic or macroscopic. The patient may not even notice microscopic bleeding, which is why we use the fecal occult blood test (TOKS) as a screening test, which detects even a small amount of blood in the stool. If the bleeding is more massive or lasts for a long time, the patient may have symptoms of anemia .

Acute peritonitis caused by tumor perforation is one of the rarer manifestations of the disease, as well as the penetration of the tumor into the surrounding area and the development of palpable resistance.

A specific symptom of KR-CA occurring in the rectal area is tenesmus .

Etiology[edit | edit source]

KR-CA occurs sporadically and in a hereditary form, when an individual has a higher genetic predisposition for developing the disease than the rest of the population. These are mainly Lynch syndrome I and II and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Hereditary background is diagnosed in about 10% of the disease[5], so sporadic occurrence dominates (90%).

However, even in the sporadic form of KR-CA, we know risk factors (RF) that increase the probability of the disease even in a genetically unaffected individual. As with most cancer diseases and with KR-CA, one of the main RFs is older age , people from 70 to 80 years of age are particularly at risk. Then:

- other diseases of the large intestine - history of intestinal adenomas and chronic intestinal inflammation, especially ulcerative colitis;

- hyperinsulinemia;

- obesity;

- smoking;

- eating habits – frequent consumption of red meat, excessive intake of animal fats and insufficient intake of fiber in the diet are especially risky.

In addition to RF, let's name protective factors . These include the previously mentioned fiber, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, folic acid, and the use of hormonal contraception .

Screening[edit | edit source]

As with all other malignancies that occur abundantly in the population, in the case of colorectal cancer (KR-CA) there was an effort to create an effective screening for detecting early stages of the disease as part of secondary prevention . Ideally, precancers (adenomas). One of the main problems with the still rather high mortality of KR-CA is the fact that in most cases it is only diagnosed at a very advanced stage. KR-CA can already be identified as one of the three malignancies for which nationwide screening is carried out in our country (further for breast cancer and cervical cancer), which effectively reduces the morbidity and mortality of this disease in the population.

- Screening methods

The basic screening methods of KR-CA in our country include:

- Test of occult bleeding in the stool (TOKS) - according to four randomized studies, thanks to the introduction of TOKS, mortality from KR-CA in people aged 50-80 years was reduced by 15-33%.[6]

- Primary screening colonoscopy – also proven to reduce the risk of KR-CA mortality.[6]

- Screening procedure

KR-CA screening is performed and paid for by the insurance company for asymptomatic men and women over the age of 50. However, all high-risk patients with a positive personal or family history are excluded from the screening program, special dispensary programs are developed for these individuals depending on their risk.[7]

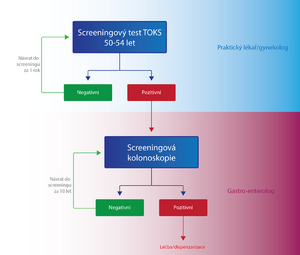

Individuals in the KR-CA screening are divided into two groups according to age, and the examination procedure differs within these two groups:

- Persons aged 50-54

- Once a year, the patient has a TOKS performed either by a general practitioner or a gynecologist. If the test result is negative (TOKS-), the same test is performed on the patient again after one year. In case of a positive result (TOKS+), the patient is sent to a specialized facility for a screening colonoscopy . If the colonoscopy result is negative, the patient will attend another screening examination in up to 10 years, if it is positive, the patient is classified in a high-risk group with a special dispensary program from the point of view of the KR-CA screening.[7]

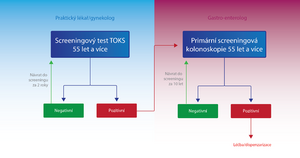

- Persons over 55 years of age

- In addition to TOKS, primary screening colonoscopy is also used for these people. The patient has a choice.

- TOKS - in the case of TOKS - either the test is repeated after two years, or a primary screening colonoscopy is performed. In the case of TOKS+, the patient is sent for a screening colonoscopy, as in the previous group.[7]

- Primary screening colonoscopy – is an alternative method to TOKS. In the case of a negative result, it is performed again in 10 years, in the case of a positive result, the patient is placed in a high-risk group with a special dispensary program from the point of view of the KR-CA screening.[7]

The importance of colonoscopy as part of screening will probably increase with the development of non-invasive virtual colonoscopy methods.[6]

Molecular-genetic screening techniques, which have significantly higher sensitivity, are being introduced into practice. They are based on the detection of mutations and aberrant methylations typical of adenocarcinoma or advanced adenoma cells.[8]

Diagnostics[edit | edit source]

Anamnesis data[edit | edit source]

Although it might seem that in the age of modern technologies such as CT , MRI and PET CT, taking an anamnesis is something archaic, there is a whole set of symptoms that can primarily guide the general practitioner to the correct diagnosis. Symptoms are often based on the location of the tumor on the large intestine:

- visible fresh blood in the stool - appears mainly in aborally localized tumors (diff. dg.: haemorrhoids , IBD );

- anemization – a relatively common phenomenon, resulting from chronic bleeding of a small scale from an ulcerated tumor, typical especially for tumors of the cecum and the right half of the colon, where the intestine has a larger lumen, and therefore the tumor has enough time for its growth before it starts to cause problems such as passage disorders;

- changes in the frequency of defecation - it can be both constipation and diarrhea, again it is more typical for the left half of the colon (descendents, sigmoid, rectum, which have a narrower lumen than the previous parts of the colon), for example, the patient tells the doctor that he has had a bowel movement all his life day and last 2 months hardly twice a week;

- tenesmus – in rectal cancer ;

- weight loss – a fairly non-specific symptom, but common in a number of oncological diseases (not only GIT);

- dyspeptic problems, general weakness, cachectization, ...

- intestinal perforation or ileus can unfortunately also be a condition that leads to the detection of malignancy, these are advanced cases, it is a very negative prognostic sign.[9]

Investigation methods[edit | edit source]

- Physical exam

Symptoms of general anemia such as paleness of the conjunctiva and skin, cachectization.[10] A per rectum examination alone can reveal a tumor in the rectal area or reveal blood in the stool[10], therefore, in the case of suspected GIT pathology, it should not be neglected by general practitioners and certainly not by surgeons. The importance of a per rectal examination as a screening examination has not been documented, but in a symptomatic individual it is a basic examination that should always be performed.[10]

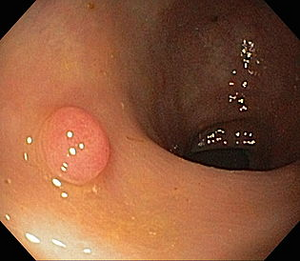

- Colonoscopy

The benefit of this examination is almost priceless, it is the examination of first choice . In addition to diagnostics (visualization and taking a biopsy), in some special cases it also enables a curative intervention consisting in removing pre-cancer or even a tumor (T1). With colonoscopy, an endosonography probe can also be used, thanks to which the depth of infiltration in the intestinal wall and possibly other organs can be determined as part of staging (primarily rectal cancer). Furthermore, ink can be applied to the site of the tumor with the help of colonoscopy, which will make it easier for surgeons to find it during the operation.

- Double-contrast irrigography

It is an X-ray examination of the abdomen with double contrast (barium suspension and air), it is performed at times when, due to obturation of the lumen or poor anatomical conditions, it is not possible to perform a colonoscopy. The examination must be supplemented with a rectoscopy, due to possible rectal tumors. The disadvantage is mainly the fact that it is not possible to take biopsy samples or to remove any polyps.

- Laboratory

In addition to signs of anemia (hypochromic, microcytic) from chronic bleeding[10] there are probably tumor markers . In the case of colorectal cancer, it is mainly the serum concentrations of CEA and Ca 19–9 . It is very important to realize that their contribution is not in the diagnosis of the disease, as they are non-specific. For example, elevated Ca 19–9[10] occurs not only in pancreatic and biliary carcinoma, but even in benign biliary obstruction. The benefit is therefore in monitoring the effects of therapy (decrease = effective chemotherapy, increase = disease relapse) and then also a prognostic benefit. High CEA at the time of disease diagnosis is a negative prognostic factor.

- CT

CT examination is important in detecting nodal and distant metastases , especially in the liver , lungs , bones and CNS . This will definitely determine the therapy strategy (curative resection versus palliation, use of neoadjuvant, adjuvant). We perform CT of the abdomen and, in the case of rectal cancer, preoperative CT of the small pelvis, to evaluate the extent of the tumor and possible metastatic spread. According to the results, a decision is made on possible neoadjuvant radiotherapy for more extensive rectal cancers.

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging dominates in rectal cancer. Here, it is absolutely important to determine the degree of infiltration of the organs of the small pelvis (bladder, ureter, vagina, but also the os sacrum), perform staging and decide on the type of resection.

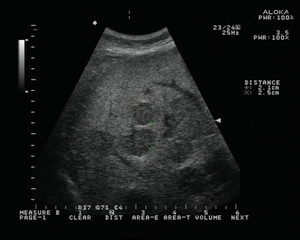

- Ultrasound

Classic sonography of the abdomen is important for detecting liver involvement by metastases , especially preoperatively and for evaluation of retroperitoneal nodes.

- Endosonography

Endoscopic sonography is especially important for rectal cancers. Thanks to this technique, it is possible to determine the depth of tumor invasion, i.e. which layer of the intestinal wall it reaches, or if it does not affect nearby lymph nodes or surrounding organs. It thus serves to determine the staging of the disease and plan the subsequent surgical procedure.

- X-ray of the chest

It is used to rule out metastatic involvement of the lungs , we perform it in a back-to-front projection. Also as a pre-operative examination.

Pathology[edit | edit source]

Precancerosis[edit | edit source]

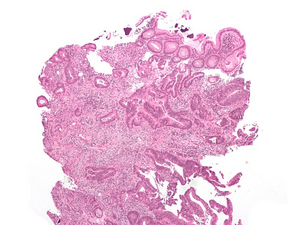

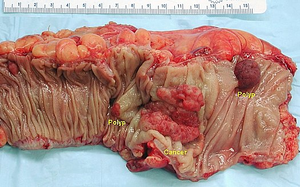

Dysplastic adenomas (tumor polyps) and other intraepithelial neoplasias, such as DALM (Dysplasia Associated Lesions or Masses) in ulcerative colitis , are considered precancerous . The risk of their malignant transformation is closely related to the degree of dysplasia . Colonic resection, visible one exophytically growing carcinoma and two adenomatous polyps

Based on the nature of the growth, possible complications of the disease can be deduced. From the point of view of macroscopy, we divide KR-CA into three groups:

- exophytic (polyposis) – the main risk is obstruction of the lumen of the intestine ( ileus ) and, rarely, intussusception of the intestine;

- excavated (exulcerated) – the risk is mainly bleeding and perforation of the intestinal wall with subsequent peritonitis ;

- flat (infiltrating) - they can remain clinically silent for a long time.

As annular cancer we mainly call left-sided cancers growing around the entire circumference of the intestine and thus leading relatively early to stenoses with all the consequences. On the contrary, right-sided carcinomas grow primarily exophytically.

- Tumor localization according to frequency [5]

- left colon – 64%;

- rectum – 30%;

- sigmoideum – 26 %;

- descending colon – 8%;

- colon transverzum – 13 %;

- ascending colon – 9%;

- blind – 14%.

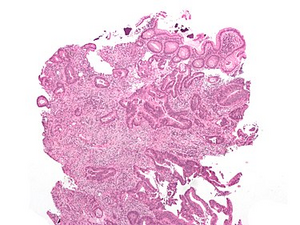

Microscopy[edit | edit source]

Histology: tubular adenocarcinoma, HE stained Microscopically, it is mainly adenocarcinoma (in 95% )[1], then we distinguish their differentiation :

- G1 – well differentiated (tubular or papillary);

- G2 – moderately differentiated;

- G3 - poorly differentiated (solidly arranged) - with worse prognosis.

We also have several more rare types of KR-CA – mucinous (mucous-forming) adenocarcinoma (which, as the name suggests, is characterized by the formation of extracellular mucus), adenosquamous carcinoma and ring cell carcinoma.

Staging[edit | edit source]

We normally use 2 classification systems to classify KR-CA

- TNM classification ,

- Dukes System .[12]

| Stage | Description |

| Stage A | tumor bounded by the intestinal wall |

| Stage B | the tumor invades or penetrates the serosa |

| Stage C1 | tumor + positive pericolic lymph nodes |

| Stage C2 | tumor + positive perivascular nodes |

| Stage D | distant metastases |

- Comparison of TNM classification and Dukes system [2]

| Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 | Dukes A |

| Stage 1 | T1 | N0 | M0 | Dukes A |

| T2 | N0 | M0 | DukesA | |

| Stadium 2 | T3 | N0 | M0 | Dukes B |

| T4 | N0 | M0 | Dukes B | |

| Stadium 3 | T1–4 | N1–3 | M0 | Dukes C |

| Stadium 4 | T1–4 | N1–3 | M1 | Dukes D |

Metastases[edit | edit source]

KR-CA metastasizes, like most cancers, primarily lymphogenically – to local lymph nodes. Later, then to distant lymph nodes and hematogenously, most often to the liver and lungs . Advanced disease can spread through the peritoneum (so-called carcinomatosis of the peritoneum ). Rectal carcinomas have a tendency to grow into the surrounding organs (vagina, uterus, ureter, bladder, but also the os sacrum). In women, the occurrence of metastases in the ovaries is also typical . The metastatic process and complications related to it can in some cases be detected even earlier than the primary tumor itself.

Therapy[edit | edit source]

The method of treatment of KR-CA can only be determined after a complete examination of the patient and determination of the staging of the disease. Each patient should be consulted at an indication seminar, and the resulting treatment should be the result of a consensus of an oncologist, surgeon, gastroenterologist, and possibly also a pathologist. The therapeutic procedure must also always depend on the patient's general state of health and his wishes.

Treatment modalities used to treat KR-CA include endoscopic , surgical and oncological methods . As a rule, the tumor mass is removed first, either endoscopically or, more often, surgically, followed by systemic oncological treatment. In the case of extensive tumors, surgical treatment is preceded by neoadjuvant oncological therapy .

Therapy procedures for KR-CA located in the colon and in the rectum differ slightly.

Endoscopic treatment[edit | edit source]

Its importance is irreplaceable, especially in the diagnosis of diseases and the subsequent dispensary of patients after treatment. It is mainly used for the curative treatment of precancers (adenomas) or very early stages of KR-CA (carcinoma in situ, pT1), or for palliative treatment to open intestinal stenoses caused by a tumor (insertion of a stent).

- Curative treatment

Depending on the extent of the lesion, we use:

- polypectomy (EPE),

- endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR),

- endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) – removal of the polyp together with the submucosa.

In patients with a diagnosis of KR-CA pT1, we decide between an endoscopic or surgical solution based on other parameters. Endoscopic treatment is sufficient for benign tumors, however, for so-called high-risk pT1 carcinomas, we proceed with a subsequent surgical solution. High-risk cancer criteria:

- incomplete removal or partial removal (not en block);

- distance from resection margins 1 mm and less;

- low differentiation;

- evidence of invasion into lymphatic vessels in a histological specimen.

In these patients, we perform surgical resection with radical lymphadenectomy, as well as in more advanced stages of KR-CA.

- Palliative treatment

The application of a metallic stent is used either in acute intestinal obstructions to wait out the time until surgical solution, or in inoperable and generalized cancers in the last stages to improve the patient's quality of life. However, according to various studies, the usefulness of these procedures is somewhat questionable. It should only be used in carefully indicated cases after interdisciplinary consultation. Patients indicated for biological treatment with bevacizumab have been shown to have a higher risk of perforation.[13]

Surgical treatment[edit | edit source]

Oncoradical resection is still the only curative treatment for colorectal cancer (with the exception of very early stages that can be solved endoscopically, see the previous paragraph). It is always indicated when it is possible to perform a curative radical (R0) resection , i.e. to remove the entire tumor mass. Possibly also for palliative reasons, similar to endoscopic treatment, to open the intestinal lumen and thereby prolong and improve the patient's quality of life.

- Colon resection

For colon cancer, we use radical resection of the affected section of the intestine together with the removal of the hinge (mesocolon). The advantage of this procedure is the removal of a larger number of lymph nodes (at least 12), the removal of potentially tumor-damaged tissue and the limitation of postoperative tumor spread. Radicality is observed even in the earlier stages (T1, T2). If the tumor is unfavorably located in the basin of two supplying arteries, we proceed to even more radical procedures - extended resection or subtotal colectomy(removal of the entire colon, leaving the rectum and establishing an ileorectal anastomosis). The distance at the aboral end should be at least 5 cm from the tumor. The extent of resection is determined by the extent of dissection of the lymph nodes (and vessels) along the arterial supply, when the ligation occurs near the distance between the arterial trunks (high ligature):

- right hemicolectomy - ligature of the ileocolic artery , dextra colic artery and dexter ramus arteriae colicae mediae (tumor of the ascending colon);

- extended right hemicolectomy - ligature of the ileocolic artery , dextra colic artery and, in addition, the medial colic artery (for tumors in the flexura coli dextra );

- left hemicolectomy - ligature of a. colica sinistra (descending colon tumor);

- extended left hemicolectomy - ligature of the sinistra colic artery and medial colic artery (tumor at the sinistra coli flexura );

- sigmoid resection - inferior mesenteric artery ligature .[14]

The laparoscopic approach is a used alternative to the classic procedure, especially for left-sided colon tumors.[13]

- Rectal resection

The most used procedure is total mesorectal excision (TME) , which significantly reduces the occurrence of local recurrences. The prognostic factor for the success of TME is mainly the positivity of the resection margins. Nowadays, we use modern mini-invasive, robotic and laparoscopic methods , which are still radical enough, but at the same time less mutilating for the patient. Surgical procedures can be divided into:

- Curative powers (potentially):

- standard operation – resection of the rectum (+ mesorectum), can be with amputation of the sphincter, but also sphincter-preserving (it is also sufficiently oncoradical);

- extensive surgery – resection of the rectum, mesorectum and abdominopelvic lymph nodes and vessels;

- ultra-extensive surgery - additionally with resection of the internal iliac vessels.[14]

- Palliative procedures consist of:

- removal of the tumor - in most cases it is better to remove the tumor, even if curative resection is excluded due to the staging of the disease or the general condition of the patient, every growing tumor threatens the patient with the formation of an ileum , perforation of the intestinal wall, tumor disintegration (necrosis);

- solving an obstruction in the passage of the intestine (it is a tumor) - with a stoma or bypass;

- pain treatment.

- Resection of liver metastases

The liver is the organ where we most often find KR-CA metastases, and their treatment is closely related to the patient's prognosis.

- Standard preoperative examination [2]

- Colonoscopy with biopsy - if not possible, double-contrast irrigography ,

- sonography of the liver

- CT scan of the liver – in case of an unclear finding or a finding of liver metastases on sono,

- CT scan of pelvis ,

- RTG plic

- CT lung – when metastases are found on X-ray

- bronchoscopy – when metastases are suspected, to rule out duplication,

- urological examination – in case of hematuria or urological problems with suspected disease progression,

- gynecological examination ,

- determination of oncomarkers – CEA, CA 19–9,

- in rectal cancer: transrectal sonography , anorectal manometry .

Oncological treatment[edit | edit source]

Almost every patient with KR-CA undergoes oncological treatment in one of its forms – radiotherapy , chemotherapy , biological treatment . According to the treatment sequence, we distinguish between neoadjuvant, adjuvant and separate oncological treatment. Radiotherapy is especially useful for rectal cancer, as it is highly sensitive to it and, moreover, has a high susceptibility to locoregional spread (colon cancer tends to establish distant metastases), we apply a dose of 30 Gy.[15]

- Neoadjuvant treatment

We use neoadjuvant treatment especially for rectal cancer - either radiotherapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy (ie chemoradiotherapy). In the case of extensive tumors (T3–T4, N+), during neoadjuvant (pre-operative) treatment, the tumor mass is reduced (so-called downstaging) , and thus a better operability of findings (higher percentage of sphincter-preserving surgery), an increase in the percentage of curative resections and a lower incidence of local recurrences . However, the overall longer survival of patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy was not confirmed.[13] The combination of chemo- and radiotherapy is accompanied by somewhat higher toxicity. In general, we have to consider the indication of neoadjuvant therapy in relation to the patient's condition, so that it does not significantly worsen his quality of life. It is the chemotherapeutic agent of choice5-fluorouracil (5-FU), alternatively capecitabine (po), possibly in combination with oxaliplatin or irinotecan [15]. Especially in combinations like FOLFOX (leucovorin, 5-FU, oxaliplatin).

Leucovorin is a biomodulator and is added to enhance the effect of 5-FU and reduce toxicity.

- Adjuvant treatment

If it is necessary after surgical treatment, systemic treatment comes next, the aim of which is to remove possible micrometastases, prevent further spread of the disease or possible relapse. The decision to start adjuvant treatment is again based on the patient's condition and tumor characteristics. It is generally recommended especially for stage III, where it increases long-term survival without signs of disease by up to 30%, and for stage II tumors with a high risk of recurrence.[13] Adjuvant chemotherapy improves 5-year survival by 10%.[2]

- Separate oncological treatment

We use palliative stand-alone oncological treatment in patients with inoperable advanced findings, extending both the median disease progression and the median survival.[13]

- Targeted treatment

A novelty in the treatment of KR-CA in the last 10 years is the introduction of targeted therapy, sometimes also referred to as biological therapy . When applied together with chemotherapy, it increases its effectiveness (increasing treatment response and prolonging the median survival of patients). The principle of targeted treatment is influencing specific signaling pathways necessary for tumor growth. In the Czech Republic, three drugs are now used for targeted treatment: bevacizumab (an antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor A – VEGF-A), cetuximab and panitumumab (epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors – EGFR).[16]

Summary[edit | edit source]

General risk factors:

- less than 12 resected lymph nodes;

- low degree of tumor differentiation (grades 3 and 4);

- tumor growth through the entire intestinal wall (T4);

- intestinal perforation or obstruction as the primary manifestation of the tumor;

- angioinvasion, lymphangioinvasion or perineural invasion;

- unknown resection margins;

- elevated level of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA);

- mucinous component of the tumor.

Treatment strategy according to disease staging at the time of diagnosis[17]:

| St. I | surgical treatment |

| St. II | surgical treatment (in case of N1 NX followed by chemotherapy) |

| St. III | surgery and always chemotherapy |

| St. IV | resection, or induction therapy and then resection, or palliative treatment |

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

The five-year survival of individuals with KR-CA varies according to the stage at which the disease is detected.[2]

| Stage | Five-year survival |

|---|---|

| St. 0 a 1 | 80-90% |

| St. 2 | 60-80% |

| St. 3 | 50-60% |

| St. 4 | 4-10% |

In general, there is a much greater chance of five-year survival in individuals who are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis (90%) compared to individuals who have had problems lasting three (40%) or seven (25%) months at the time of diagnosis.[2] Prevention and a screening program are therefore important for this disease.

Links[edit | edit source]

Related articles[edit | edit source]

- Treatment of liver metastases in colorectal cancer

- Vienna Classification of Gastrointestinal Neoplasia (2002)

External links[edit | edit source]

- Colorectal cancer - article in Oncology Care magazine

- Zdravi.e15 - Colorectal cancer therapy (4/2012)

- Atlas of Pathology for Medical Students - Colon

- Cancer research UK - Duke`s stages of bowel cancer

- Česká společnost HPB chirurgie: Návrh standardu chirurgické léčby kolorektálního karcinomu

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ a b c d e WORLD CANCER RESEARCH FUND INTERNATIONAL. World Cancer Research Fund International : Colorectal cancer statistics [online]. ©2015. The last revision 16/01/2015, [cit. 2015-11-13]. <https://www.wcrf.org/int/cancer-facts-figures/data-specific-cancers/colorectal-cancer-statistics>.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Česká gastroenterologická společnost ČLS JEP. Kolorektální karcinom - diagnostika a léčba [online]. [cit. 2015-11-13]. <http://www.cls.cz/seznam-doporucenych-postupu>.

- ↑ svod.cz. Epidemiologie zhoubných nádorů v České republice : Incidence a mortalita [online]. Masarykova univerzita, ©2011. The last revision 2011, [cit. 2011-11-30]. <http://www.svod.cz/>.

- ↑ a b svod.cz. Epidemiologie zhoubných nádorů v České republice : Incidence a mortalita [online]. Masarykova univerzita, ©2012. The last revision 2012, [cit. 2015-11-13]. <http://www.svod.cz/>.

- ↑ a b ČEŠKA, Richard, et al. Interna. 1. edition. Praha : Triton, 2010. pp. 855. ISBN 978-80-7387-423-0.

- ↑ a b c ČEŠKA, Richard, et al. Interna. 1. edition. Praha : Triton, 2010. 412 pp. pp. 855. ISBN 978-80-7387-423-0.

- ↑ a b c d DUŠEK, L., et al. Kolorektum.cz : Kolorektum.cz – Program kolorektálního screeningu v České republice [online]. ©2015. The last revision 23. 2. 2015, [cit. 2015-11-11]. <http://www.kolorektum.cz/index.php?pg=pro-odborniky--organizace--screeningovy-proces>.

- ↑ IMPERIALE, Thomas F. – RANSOHOFF, David F. – ITZKOWITZ, Steven H.. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med [online]. 2014, vol. 371, no. 2, p. 187-8, Available from <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25006736>. ISSN 0028-4793 (print). PMID: 1533-4406.

- ↑ BURKHITT, H. George – G QUICK, Clive R.. Essential surgery: problems, diagnosis and managment. 4. edition. Edinburgh : New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2007. 402-412 pp. pp. 793. ISBN 9780443103469.

- ↑ a b c d e f ČEŠKA, Richard, et al. Interna. 1. edition. Praha : Triton, 2010. 409-412 pp. pp. 855. ISBN 978-80-7387-423-0.

- ↑ ZEMAN, Miroslav, et al. Speciální chirurgie. 2. edition. Praha : Galén, 2006. 299-304 pp. pp. 575. ISBN 80-7262-260-9.

- ↑ ZEMAN, Miroslav, et al. Speciální chirurgie. 2. edition. Praha : Galén, 2006. 300 pp. pp. 575. ISBN 80-7262-260-9.

- ↑ a b c d e ZAVORAL, Miroslav, et al. Zdraví E15 : Terapie kolorektálního karcinomu [online]. ©2012. The last revision 6.4.2012, [cit. 2015-12-02]. <https://web.archive.org/web/20160331222721/http://zdravi.e15.cz/clanek/postgradualni-medicina/terapie-kolorektalniho-karcinomu-464247>.

- ↑ a b ŠIMŠA, Jaromír. Onkochirurgie [lecture for subject Chirurgie-předstátnicová stáž, specialization Chirurgie, the 1st Faculty of medicine Charles University]. Praha. 2011-10-08.

- ↑ a b LIPSKÁ, Ludmila – VISOKAI, Vladimír, et al. Recidiva kolorektálního karcinomu: Komplexní přístup z pohledu chirurga. 2. edition. Praha : Grada, 2009. pp. 456. ISBN 978-80-247-3026-4.

- ↑ -. - [online]. [cit. 2016-1-17]. <https://web.archive.org/web/20160331222721/http://zdravi.e15.cz/clanek/postgradualni-medicina/biologicka-lecba-kolorektalniho-karcinomu-466755>.

- ↑ ŠMAKAL, Martin. Komplexní léčení nádorů - role onkologa [lecture for subject Chirurgie-předstátnicová stáž, specialization Chirurgie, the 1st Faculty of medicine Charles University]. Praha. 2011-10-21.

Bibliography[edit | edit source]

- ČEŠKA, Richard, et al. Interna. 1. edition. Praha : Triton, 2010. 855 pp. pp. 409-412. ISBN 978-80-7387-423-0.

- POVÝŠIL, Ctibor. Speciální patologie. 2. edition. Praha : Galén, 2007. 430 pp. pp. 167-169. ISBN 978-807262-494-2.

- Česká gastroenterologická společnost ČLS JEP. Kolorektální karcinom - diagnostika a léčba [online]. [cit. 2015-11-13]. <http://www.cls.cz/seznam-doporucenych-postupu>.

Recommended literature[edit | edit source]

- PETRUŽELKA, Luboš – KONOPÁSEK, Bohuslav. Klinická onkologie. 1. edition. Praha : Karolinum, 2003. 274 pp. ISBN 80-246-0395-0.

- KRŠKA, Zdeněk – HOSKOVEC, David, et al. Chirurgická onkologie. 1. edition. Praha : Grada, 2014. 904 pp. ISBN 978-80-247-4284-7.

- KLENER, Pavel. Základy klinické onkologie. 1. edition. Praha : Galén, c2011. ISBN 9788072627165.