Sideropenic anemia

Sideropenic anemia (also known as Iron-deficiency Anemia) is a condition caused by a disorder of hemoglobin synthesis due to iron deficiency. This is the most common type of anemia in children.[1]

Sideropenic anemia:

Sideropenic anemia 2:

Causes of emergence[edit | edit source]

Insufficient supply of iron in food is rare in the czech republic country. Substances that inhibit resorption (phosphates, phytates) can cause reduced intake. It is more often manifested in malabsorption (Celiac disease, Crohn's disease, after a resection of the stomach or intestines). It also occurs with excessive blood loss during chronic bleeding (peptic ulcers, hemorrhoids, GIT cancer, menorrhagia, metrorrhagia). Iron deficiency also manifests itself if the organism has increased demands for hematopoiesis (during pregnancy, in childhood).

- Causes of sideropenic anemia in children

- Malabsorption - treatment with antacids, drugs that increase gastric pH, drinking tea and coffee.

- Insufficient/unavailable iron stores - bleeding, epistaxis, gastric and duodenal ulcers, Meckel's diverticulum, cow's milk protein allergy, parasites, Helicobacter pylori infection, esophageal varices, tumors and polyps of the digestive system, inflammatory diseases of the GIT, AV malformations, diverticulitis, hemorrhoids, heavy menstrual bleeding, infections/tumors of the uropoietic tract, pulmonary hemosiderosis

- Congenital/acquired disorders of iron metabolism – atransferrinemia, disorders of heme synthesis.[1]

Iron in the human body[edit | edit source]

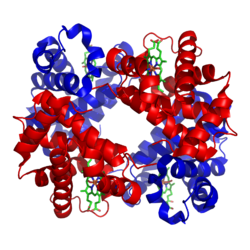

There are a total of 3-4 g of iron in the body, most of which is found in hemoglobin. Iron recycling from decomposing erythrocytes yields 20 mg per day. In adults, <5% of the total iron comes from the diet, while in an infant it is around 30%.

A full-term newborn has sufficient iron reserves for the first 6 months, after which a dietary supply of iron is necessary. Premature babies have a lower hemoglobin concentration and lower iron reserves, therefore iron depletion already occurs around the 2nd month. Breast milk and cow's milk have the same iron content, but cow's milk is more difficult to absorb. The iron content in breast milk decreases after 5 months of breastfeeding. Boys need a higher supply of iron during puberty due to the increase in muscle mass and myoglobin. Girls need a higher iron intake due to losses during menstrual bleeding.[1]

Clinical picture and diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Microcytic hypochromic anemia. The erythrocyte volume distribution width (RDW) is usually increased due to anisocytosis. Thrombocytosis (500-700×109/l) is relatively common.[1]

- Prelatent sideropenia – deficiency of stored iron (reduced ferritin level, other values in the norm).

- Latent sideropenia – deficiency of stored and stored iron in macrophages. This leads to iron deficiency in erythropoiesis (decreased ferritin, iron and increased soluble transferrin receptor sTFR), without anemia.

- Sideropenic anemia – deficiency of stored and erythrocyte iron results in a drop in the level of hemoglobin, hematocrit, reduced mean erythrocyte volume (MCV), reduced hemoglobin content in erythrocyte (MCH). Furthermore, it is manifested by a low level of iron, ferritin and an increase in the total binding capacity by stimulating the production of transferrin in the liver and increasing sTFR. Transferrin saturation drops below 16%, hepcidin level drops.[1]

There is a reduced amount of reticulocytes in the blood, as more erythroblasts are found in the bone marrow. The marrow is normocellular, and will be hypercellular in anemia due to increased losses. Depletion of stored iron is characteristic (macrophages do not show hemosiderosis). It is mainly manifested by tissue hypoxia (eg tiger heart).

In children, it manifests itself most often between 6 months and 3 years of age and then in puberty. Iron deficiency during the child's growth period can lead to growth retardation, psychomotor development and cognitive function disorders (negative effect on learning to concentrate). Damage to the epithelium leads to atrophy of the papillae of the tongue and increased brittleness of the nails.[1]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Anemia of inflammatory diseases – classically normocytic normochromic, in a third of patients microcytic hypochromic, but elevated ferritin and hepcidin.

- Thalassemia - microcytic hypochromic anemia, lower RDW, in the smear typical target-shaped erythrocytes and basophilic stippling of erythrocytes.

- Lead poisoning - microcytic/normocytic normochromic anemia; behavioral changes, convulsions, kidney damage, abdominal pain and vomiting.

- Sideroblastic anemia - hypochromic erythrocytes, increased serum iron, increased transferrin saturation, coronal sideroblasts in the bone marrow (the "coronas" are iron-packed mitochondria).[1]

Therapy and prevention[edit | edit source]

Prevention is the addition of iron to infant formula, the introduction of meat and vegetable side dishes, cereals and milk products enriched with iron, the exclusion of non-adapted cow's milk from the infant diet and the prophylactic administration of iron in premature babies.

Example of Substitution: oral preparations of iron (fasting) with simultaneous use of ascorbic acid, which increases iron resorption.

- Preparation of substitutions

- Divalent iron salts - ferrous sulfate (Aktiferrin, Ferronat);

- Iron in a complex with polysaccharides (Maltofer) – fewer side effects;

- Parenteral administration of trivalent Fe – in case of proven malabsorption, significant blood loss, noncompliance, etc.. Anemia is corrected as quickly as with oral substitution.

- Side effects

- Feeling of fullness, nausea, constipation or diarrhea. Acute iron poisoning can manifest itself in severe gastrointestinal symptoms and systemic toxicity. We use an antidote that binds toxic free iron

The effect of the treatment is evaluated by the rise of reticulocytes (4th - 10th day of treatment), gradual rise of hemoglobin (by 20 g/L in 4 weeks). It usually takes a total of 3-5 months to continue to replenish iron stores.[1]

Summary Video[edit | edit source]

Links[edit | edit source]

Related articles[edit | edit source]

Footnotes[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ČEŠKA, Richard – ŠTULC, Tomáš. Interna. 2. edition. 2015. 909 pp. ISBN 978-80-7387-895-5.

- PASTOR, Jan. Langenbeck's medical web page [online]. [cit. 12.4.2010]. <http://langenbeck.webs.com>.