Melanoma

Malignant melanoma is a cancer that results from neoplastic proliferation of melanocytes. It is one of the neuroectoderm tumors. Malignant melanoma mainly affects the skin, but can also affect the eye, ear, leptomenings, GIT and the mucous membranes of the mouth or genitals. The incidence of melanoma is increasing, affecting mainly the white population.

Melanoma occurs in four basic histological types: superficially spreading melanoma , lentigo maligna melanoma , acrolentiginous melanoma and nodular melanoma . The basis of therapy is surgical resection of the tumor together with a sufficient margin of the adjacent skin, or resection lymph nodes. Adjuvant treatment with interferon α, specific vaccines, BRAF inhibitors (Vemurafenib) and CTLA-4 blockers (Ipilimumab) are contemplated.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The incidence of melanoma is growing worldwide . In the white population in the United States, the incidence of melanoma has more than tripled in the last twenty years. The incidence of melanoma shows geographical differences. While in North America there are 6.4 new cases per 100,000 men and 11.7 new cases per 100,000 women, in Australia and New Zealand it is already 37.7 cases per 100,000 men and 29.4 cases per 100,000 women.[1] The incidence of melanoma in the Czech Republic in 2006 was 18.4 per 100,000 men and 15.6 per 100,000 women.[2]

Malignant melanoma accounts for approximately 4% of all skin tumors, but is responsible for up to 73% of skin cancer deaths. Globally, survival is higher in developed countries (91% in the US, 81% in Europe) than in developing countries (approximately 40%). Lower mortality in developed countries is mainly due to greater public awareness, which leads to earlier diagnosis and treatment.[1]

Malignant melanoma mainly affects the white population. The prevalence of melanoma in the Hispanic population in the United States is approximately six times lower than in the white population. It is even up to twenty times lower in African Americans. However, mortality from malignant melanoma in the Hispanic and African American populations is higher than in the white population. The reason is more frequent acral melanoma and more advanced disease.[1]

Under the age of 39, melanoma is more common in women, and from the age of 40 is more common in men. Overall, women are affected slightly more often (male to female ratio, 0.97: 1), however, mortality is higher in men.[1]

The Median diagnosis of melanoma is 59 years, however in women between the ages of 25 and 29, melanoma is the most common type of cancer, and between 30 and 34 is the second most common type of cancer after breast cancer. Malignant melanoma affects more elderly individuals who succumb to the disease even more often. Therefore, older people should be the main target of secondary melanoma prevention.[1]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

The pathophysiology of melanoma development is not fully understood. Multiple pathogenetic mechanisms of melanoma development are thought. Melanoma occurs not only on sun-exposed skin, where UV radiation is the main pathogenetic factor, but also in places that are relatively protected from radiation (torso).[3]

Malignant melanoma is accompanied by mutations in the BRAF, NRAS and KIT genes. The individual representation of mutations depends on the method of exposure to sunlight. While the BRAF mutation occurs more with intermittent sun exposure and is more common in superficially spreading melanoma, the KIT mutation occurs more with chronic exposure or relatively unexposed skin and is more common in nodular melanoma. [3]

Melanoma arises either by malignancy of an already present melanocytic nevus or more often de novo (in more than 70% of cases).[3]

Risk Factors include:

- age over 50, [4]

- higher sensitivity to sunlight,

- excessive exposure to sunlight in childhood, bullous dermatitis after sunburn in childhood,

- increased number of atypical (dysplastic) nevi [3] or large congenital nevi (greater than 20 cm in adulthood), [4]

- familial occurrence of melanoma,

- presence of changing pigment spot, [3]

- immunosuppression,

- use of solarium. [4]

Clinical picture and histopathological types[edit | edit source]

Melanoma is most common on torso in white men, while on the lower leg or back in white women. Melanomas in Hispanics, African Americans, and Asians are most common on the plant, followed by subungual localization, palms and mucous membranes.

Melanoma is most common on torso in white men, while on the lower leg or back in white women. Melanomas in Hispanics, African Americans, and Asians are most common on the plant, followed by subungual localization, palms and mucous membranes.

Melanoma can affect both the skin and mucous membranes (such as oral) or the eye.[5]

According to the nature of growth, anatomical location of the disease and the degree of sun damage, cutaneous melanoma is divided into four basic clinicopathological subtypes:

Superficially spreading melanoma[edit | edit source]

This subtype represents approximately 70% of cutaneous melanomas and is the most common subtype of melanoma in individuals aged 30-50 years. [5]

This subtype represents approximately 70% of cutaneous melanomas and is the most common subtype of melanoma in individuals aged 30-50 years. [5]

At first, the tumor behaves like carcinoma in situ , which grows radially and does not tend to metastasize. At this stage, melanoma can last for months to years. It most often occurs on the torso of men or on the shins of women. Formed on intermittent sun exposure. [5]

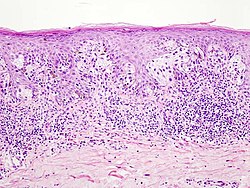

It often shows warning signs of ABCD (see diagnosis). It is either flat or slightly elevated. It is usually larger than 6 mm. Histologically, the pagetoid distribution of atypical melanocytes in epidermis is evident (similar to scattered shotgun shots, so-called "buckshot scatter"). [5]

Nodular melanoma[edit | edit source]

Represents 15-30% of skin melanomas.[5]

Nodular melanoma lacks a carcinoma in situ phase, grows relatively rapidly, and invades deeper skin structures. The most common locations are the legs and torso of both men and women. Formed on intermittent sun exposure. [5]

It usually does not show the warning signs of ABCDE and can easily escape attention. It usually manifests as brown-black papula or even a nodular formation that easily ulcerates and bleeds. In addition, the lesion may be amelanocytic, i.e. without pigment. [5]

Lentigo maligna melanoma[edit | edit source]

The incidence of lentigo maligna melanoma is increasing. It mainly affects older individuals around the age of 65. [5]

Lentigo maligna is a carcinoma in situ with radial growth without a tendency to metastasize. The lesion is usually larger (1-3 cm) in dark brown to black pigmentation, although hypopigmentation is no exception. At this stage, lentigo maligna lasts for at least 10-15 years before a dermal invasion occurs and lentigo maligna melanoma develops, forming a raised blue-black nodulus on the surface. Typical localization is head, neck and arms. It is formed during chronic sun exposure. [5]

Acrolentiginous melanoma[edit | edit source]

The least common subtype of melanoma in the white population, but the most common subtype of melanoma in the dark-skinned population (African Americans, Hispanics, Asians). [5]

At first, the tumor behaves like carcinoma in situ , which grows radially and does not tend to metastasize. At this stage, melanoma can last for months to years. It most often occurs on the palms, soles or under the nail plate (subungual melanoma). Subungual melanoma manifests as a diffuse color change or as a pigment band under the nail plate. The spread of the pigment to the proximal or lateral nail wall is referred to as the Hutchinson's trait , typical of subungual melanoma. Acrolentiginous melanoma typical of subungual melanoma, typical of subungual melanoma. Acrolentiginous melanoma Acrolentiginous melanoma , typical of subungual melanoma. Acrolentiginous melanoma similar to mucosal melanomas.[5]

Benign junctional melanocytic nevus, subungual hematoma and onychomycosis must be considered differentially diagnostically. [5]

Rare subtypes of cutaneous melanoma[edit | edit source]

They occur in less than five percent of cases.

- Desmoplastic melanoma is a rare but important subtype of cutaneous melanoma that occurs predominantly in the elderly (60-65 years of age). It mainly affects the sun's exposed skin of the head and neck. Clinically, it resembles non-melanocytic skin tumors and therefore there may be a delay in diagnosis. Desmoplastic melanoma often has perineural spread and is popular with local recurrence. Therefore, radical excision with adjuvant radiotherapy is recommended for therapy.

- Mucosal (lentiginous) melanoma.

- Malignant blue nevus.

- Melanoma arising from large congenital nevi.

- Clear cell sarcoma.

- Amelanocytic melanoma is pigment-free and can occur concurrently with any subtype of melanoma (usually nodular or desmoplastic). It can mimic basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma, dermatofibroma or even hair follicle lesions.[5]

Diagnostics[edit | edit source]

The most common warning sign of melanoma is a newly formed and changing pigment spot. Symptoms such as bleeding, itching, ulceration or pain at the site of the pigment spot may occur. The ABCDE rule has been developed for clinical use, which assesses the warning signs of melanoma:

The most common warning sign of melanoma is a newly formed and changing pigment spot. Symptoms such as bleeding, itching, ulceration or pain at the site of the pigment spot may occur. The ABCDE rule has been developed for clinical use, which assesses the warning signs of melanoma:

- A - Asymmetry (asymmetry) - the pigment spot is not symmetrical.

- B - Border irregularity - the edges of the spot are uneven, serrated or vaguely demarcated.

- C - Color variegation - the color is not uniform, it shows different shades of skin, brown and black. The white, red or blue color of the pigment spot is a worrying finding.

- D - Diameter - diameter greater than 6 mm is characteristic of melanoma, although smaller diameters may occur. Any stain growth deserves examination.

- E - Evolution - the pigment spot changes over time. This point is especially important in nodular melanoma or amelanocytic melanoma (without pigment), which may lack ABCD points.

Lesions that exhibit these characteristics are considered potential melanoma.[6]

It is practical for the clinic to evaluate the warning sign of an "ugly duckling". It is a pigment spot that differs from the others in some way. It is advisable to combine this flag with the ABCDE criteria.[6]

If melanoma is suspected, a biopsy of the suspected skin or mucosa (excision with a 1-3 mm margin of healthy tissue) and a subsequent histological examination are important. In the biopsy report, we read five basic pieces of information:

- Tumor thickness in millimeters (Breslow) [7] - is the most important prognostic factor, measured from the upper limit of the stratum granulosum to the deepest point of tumor invasion. The greater this thickness, the higher the potential for metastasis and therefore the worse the prognosis.[8]

- Ulceration [7] - is the second most important prognostic factor, its presence shifts staging. [8]

- Dermal number of mitoses [7] - number of mitoses per 1 / mm 2 increases the likelihood of metastasis and worsens the patient's prognosis. Cite error: Closing

</ref>missing for<ref>tag - Microsatellite

- Anatomical degree of invasion ( Clark ) - only for tumors less than or equal to 1 mm and if the mitotic index cannot be evaluated; optional for tumors larger than 1 mm. According to statistics, it is not as prognostic for patient survival as Breslow, ulceration, mitotic index, age, sex or location of the lesion.[8]

In case of ambiguity in histology, immunohistochemical staining , for example S-100, HMB-45 ("homatropine methylbromide 45"), melan-A / Mart-1 or proliferation markers such as Ki67 (proliferating cell nuclear antigen), may help with the diagnosis.[9]

If the tumor is larger (or equal to) than 1 mm, or if the thinner tumor exhibits adverse prognostic factors such as ulceration or a higher number of mitoses, a sentinel node biopsy is performed to help us determine staging of the disease.[10]

Elevated levels of serum LDH in biochemical examination are a negative prognostic marker, they are associated with shorter survival time. [10]

Indications for imaging tests such as X-ray , CT , MRI or PET are considered individually, for example to assess the presence of metastases. [10]

Staging[edit | edit source]

According to histology, melanoma is divided into stages 0 – IV:

- Stage 0 is carcinoma in situ.

- Stage I and II have invasion depth as a criterion.

- Stage III affects regional lymph nodes.

- Stage IV represents distant metastases in the skin, subcutaneous tissue, nodules, visceral area, skeleton or CNS.

In addition, the individual stages have subgroups according to the presence of various features, such as the presence of ulceration, the number of mitoses or the value of LDH (lactate dehydrogenase). For example, a 2.01-4 mm wide lesion without ulcerations is evaluated as stage IIA, but the same lesion with ulcerations is evaluated as IIB.[11]

Therapy[edit | edit source]

Surgery[edit | edit source]

The basic method of therapy for a localized form of malignant melanoma is surgical resection of a tumor site with a sufficiently wide margin of healthy skin. For in situ carcinoma, this margin is 5 mm wide. For "low risk" melanomas of depth (Breslow) 1 mm and less, it is recommended to excise 1-cm margin wide. For melanomas 1 mm or more deep, a 2 cm margin is recommended. According to studies, a margin wider than 2 cm did not bring any clinical benefit. [12]

Selective lymph node dissection may improve the prognosis of patients with malignant melanoma, according to studies conducted by the WHO. [12]

Previously, the issue of regional lymphadenectomy for melanomas 1 mm or greater (Breslow) or less than 1 mm, but with negative prognostic features such as ulceration, lymphovascular invasion, or higher mitoses, has been addressed. In the 1990s, sentinel node biopsy (SLNB) methods were used for malignant melanoma, which solved this problem. [12] 99m Tc peritumoral injection is used to image the sentinel node. The radiopharmaceutical is drained into the lymph node. Perioperatively, this node can be identified by a gamma camera. The second option is to apply dyes such as methylene blue or lymphazurin, which will stain the gradient. When combining both methods, the probability of sentinel node capture is approximately 95% (influenced by anatomical location).[13]. The sentinel node thus located is removed and examined histologically or immunohistochemically for the presence of micrometastases. If the biopsy is positive, complete lymph node dissection (CLND) is performed. If the finding is negative, the nodules are left.[12]

Adjuvant therapy[edit | edit source]

Adjuvant therapy in the form of chemotherapy (dacarbazine therapy), radiotherapy, biological therapy, non-specific immunomodulation or vitamin therapy does not affect patient survival and is still the subject of research.[14]

One hope may be high-dose interferon α therapy, which statistically reduces the incidence of relapse. The disadvantage is the long-term therapy with high doses and the resulting side effects. These may be flu-like symptoms, intolerance to therapy, or induction of autoimmunity with the production of autoantibodies (antithyroid, antinuclear, anticardiolipin). The prognostic significance of induced autoimmunity in malignant melanoma is still under study. [14]

The second hope may be the application of specific vaccines that contain melanoma antigenic structures. These vaccines, as we might expect, are not important in prevention, but act as a stimulator of the immune system in advanced forms of the disease (St. III, IV). Unlike interferon therapy, it does not have as many side effects. The efficacy of the self-administered vaccines has not been demonstrated, but the combination of the peptide vaccine (gp100: 209-217 (210M)) with high-dose IL - 2 therapy is hopeful, with good results so far. [14]

The third route of research is the so-called BRAF-inhibitors (Vemurafenib), ie inhibitors of some mutated forms of serine-threonine kinases. Vemurafenib therapy significantly reduces the risk of disease progression and prolongs survival. However, this path must be complemented by further studies. [14]

The third route of research is the so-called BRAF inhibitors ( Vemurafenib ), ie inhibitors of some mutated forms of serine-threonine kinases. Vemurafenib therapy significantly reduces the risk of disease progression and prolongs survival. However, this path must be complemented by further studies.

Ipilimumab , a monoclonal antibody against cytotoxic T-cell antigen 4 ( CTLA-4 ) , can be used for metastatic or unresectable melanoma . By blocking CTLA-4, T-cell activity and proliferation are enhanced . The anti-tumor mechanism itself is non -specific , mediated by T-cell activity.

As can be seen from the previous text, the diagnosis and therapy of malignant melanoma depends on interdisciplinary cooperation among dermatologist, pathologist, surgeon, nuclear medicine specialist, oncologist, or radiation oncologist.[15]

Patients who have been diagnosed with malignant melanoma should be treated for relapse. The most common metastases occur 1-3 years after the treatment of the primary tumor. 4–8% of patients with a history of malignant melanoma will develop a new primary melanoma locus within 3-5 years. [16]